Did you know that most ear infections resolve on their own and don’t need antibiotics?

Read more

As a pediatrician, I frequently see patients who come in “just to make sure they don’t have an ear infection”. The child may be waking at night, pulling on their ears, coughing, having a fever or actually complaining of ear pain. Ear pain is one of the most common concerns that parents have. The good news is that most children who are pulling on their ears but who are not otherwise sick, do not have an infection. Even those with a common cold do not always end up with an ear infection. But when kids do get an ear infection, what does that mean and what should parents do? It’s time to talk all things ear infections with our resident Ear, Nose and Throat doctor, Dr. Matthew Brigger.

What is an ear infection?

Dr. Brigger explains that “ear infections occur when bacteria grow behind the ear drum leading to a collection of pus”, which is thick fluid created by the immune system while fighting the infection. The inflammation and pus accumulation causes “pressure [on the ear drum], pain and temporary hearing loss”. Not all red ears are infections that require intervention though. It is possible to have a viral ear infection (inflammation and pain of the ear drum) or to have clear fluid behind the ear drum, both of which can happen during a cold. The doctor diagnoses a bacterial ear infection when there is pus behind the ear drum causing it to bulge out. There should also be signs of of inflammation like pain and fever.

Typical symptoms include:

- Ear pain, which may present as fussiness in babies or toddlers who can’t describe their symptoms

- Pulling or batting at the ear

- Trouble sleeping (the pain is worse while lying down)

- Trouble hearing

- Trouble with balance

- Fever

- Fluid draining from the ear

How do kids get ear infections?

We most often see ear infections in kids who are already sick with colds.  There is actually a very good reason for that! Dr. Brigger describes it this way: “The space behind the ear drum, also known as the middle ear, is filled with air which comes from the nose through a small internal connection known as the Eustachian tube. By having air in the middle ear, our eardrum can vibrate properly.” That’s how we hear. During a cold (or allergies), congestion closes off the Eustachian tube. “When the Eustachian tube closes off, the ear can fill with fluid which then becomes infected. Due to the small size and immature nature of the Eustachian tube in children, they are more likely to get ear infections than adults.” Some kids have dysfunction of their Eustachian tubes which causes increased pressure in the middle ear even when they aren’t sick with a cold. That can also lead to an infection.

There is actually a very good reason for that! Dr. Brigger describes it this way: “The space behind the ear drum, also known as the middle ear, is filled with air which comes from the nose through a small internal connection known as the Eustachian tube. By having air in the middle ear, our eardrum can vibrate properly.” That’s how we hear. During a cold (or allergies), congestion closes off the Eustachian tube. “When the Eustachian tube closes off, the ear can fill with fluid which then becomes infected. Due to the small size and immature nature of the Eustachian tube in children, they are more likely to get ear infections than adults.” Some kids have dysfunction of their Eustachian tubes which causes increased pressure in the middle ear even when they aren’t sick with a cold. That can also lead to an infection.

How are ear infections treated?

Our treatment of ear infections has evolved tremendously. “Most ear infections are relatively minor” says Dr. Brigger “and some do not even require antibiotics.” Our current guidelines allow for pain control for 24-48 hours prior to starting antibiotics in children over 2 years of age, who do not have a history of ear problems and who are otherwise well. “In general, antibiotics will lead to resolution of the acute infection relatively quickly” once they are started and as long as the correct antibiotic is used. It can be normal for fluid to persist in the middle ear after an infection or be present during a cold, but this is “non infected ear fluid which may remain [behind the ear drum] up to several months”. Non infected fluid in the middle ear does not require antibiotics.

What are complications of ear infections?

While most ear infections are benign and will resolve on their own, some ear infections can result in complications. “Untreated ear infections can lead to rupture and scarring of the ear drum. Occasionally, repeated ear infections can lead to permanent hearing loss. In rare instances, ear infections can lead to more serious bacterial infections, including infection of the skull bones or the brain. Rarely ear infections can cause damage to the nerve that controls facial movement.” Therefore, if your child is still having pain or physical signs of an ear infection 24-48 hours after diagnosis, go ahead and give them the antibiotics prescribed. If they are already taking antibiotics, follow up with your doctor.

When does a child need ear tubes? (And really what are ear tubes?)

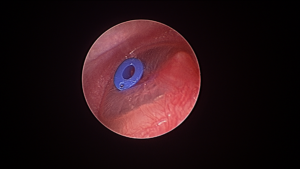

Parents (and pediatricians) become concerned when their child has multiple ear infections or has an ear infection that is hard to treat. Dr. Brigger has guidelines on when a referral to your local ENT for evaluation is needed. The treatment to prevent ear infections, along with possible complications or permanent hearing loss, is to place ear tubes. “Ear tubes should be considered when a child has frequent ear infections. In general, when children have 3 infections in 6 months or 4 infections in a year, ear tubes may be indicated. Ear tubes are also known as pressure equalization tubes and are placed through a surgical procedure that creates a hole in the ear drum to allow fluid to drain, but more importantly allows the space behind the ear drum to fill with air and equalize the pressure on both sides of the ear drum. Ear tubes are small approximately 1mm rings with flanges that hold the ring in the ear drum. Ear tubes generally last approximately 8-10 months and then fall out on their own at which point the ear drum generally heals. The small size of the ear tube still allows the eardrum to vibrate and allow normal hearing. Recovery from surgery is generally quite easy with most children resuming their normal routines the following day. Ear tubes do not prevent children from swimming as ear plugs are no longer recommended when in the water.” For more on ear tubes, click here.

So in a nutshell, if you are worried about your child’s ears, have him/her checked. Follow your doctor’s advice and if antibiotics are prescribed, finish the entire prescription. If your child is getting frequent ear infections, a referral to the Ear, Nose and Throat doctor may be needed.

All quotes are attributed to Dr. Matthew Brigger, Otolaryngologist at Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego. His bio can be found in our mutual post on Swimmer’s Ear here.